Separation, Psychology and Sin

Part One - A Fathers Lament: On the Ontology of Separation

Let me begin this series with a piece of creative writing. Forgive me in advance – I’m no poet. I don’t know much about cadence, form, or stanzas. But I do know the power of words. So, let’s call this a lament. Or maybe a cry. Definitely not a poem:

OLIVIA

My world I would give

to walk inside yours –

to love you completely

as you know love,

to sense with your senses,

to think with your thoughts,

to speak with your words,

to beat with your heart.

The greatest love I would give,

unfettered, unbound,

if only I knew how.

You are of me,

but separate.

Begotten in unity,

divided by earth.

And this is the horror of the fall –

My daughter, I love you

more than we could ever know.

One day, my daughter was sitting quietly, thinking. I asked, “What are you thinking about?” In the sincere, gentle way she can often be, she smiled a thin smile and said softly, “Nothing”.

And that was that.

In that moment, my world collapsed. My little girl, so interwoven into our lives, was now separate. In that brief, seemingly fruitless exchange lay more meaning than a thousand-page discourse on existence. I realised that no matter how much I tried to love her – no matter how good a father I strove to be, how deeply I cared and accepted – we were separate.

I realised in that moment, that at the core of her being is something that I can never experience. Something I can never grasp. At the end of my love lies a mystery – an enigma. A being I can never possess, a relationship bounded by mere empathy, affection, warmth and touch – defined by an all too painfully human love.

A love that, as far as I’m concerned, isn’t enough. A love that barely meets the criteria of what she deserves.

I feel this separation everywhere, but most sincerely in my role as a father – or more accurately, in the constant striving, and failing, to be the father I want to be. To love completely. To love honestly. To encompass my children’s being-in-the-world and touch the unity of love itself.

To take on their responsibilities, their joy, their sadness. To sacrifice my being for theirs. To understand their world as they do and be everything that they need me to be.

This self-expectation aches. It hinders. It forces me into a corner of resignation.

Battered, bruised and bleeding I throw in the towel and admit: I can never be what you need me to be – I can never love, as I desire to love.

It would be easy to dismiss this as sadness, or melancholy – but it’s more than that. It’s deeper. Older. It’s something inherent to love itself, something we have all felt in different ways:

When we long for home. When we ache for an absent lover. When words and actions fail us. When we cry and don’t know why. When we stare into the eyes of another and are overwhelmed by their sheer presence. Burdened by mere existence.

What I want to ask you is this: have you ever faced the void – the space between us – and simply sat there, paying attention?

If you have, then you’ll understand me when I say – it’s terrifying.

We all face this at some point in our lives, some more consciously than others, perhaps, but none of us escape it.

What I want to explore here is an old idea: that we don’t just face this separation – but that we embody it.

It’s not something that we experience. It’s something that we are.

Nietzsche’s Footbridge

So what is this distance about? This separation? This striving for what cannot be realised?

The answer, I think, is that the separation we feel isn’t epistemological – a matter of perception – but ontological: woven into the very fabric of being itself.

How I feel regarding my children is not a flaw or failing particular to me, but a tragic attribute of our human nature. As Nietzsche implies in The Joyous Science, we are embedded in separation:

“There was a time in our lives when we were so close that nothing seemed to obstruct our friendship and brotherhood, and only a small footbridge separated us. Just as you were about to step on it, I asked you: “Do you want to cross the footbridge to me?” —Immediately, you did not want to anymore; and when I asked you again, you remained silent. Since then mountains and torrential rivers and whatever separates and alienates have been cast between us, and even if we wanted to get together, we couldn’t. But when you now think of that little footbridge, words fail you and you sob and marvel”

Nietzsche is at his poetic best here, giving us enough to chew on, but not enough for a nutritious meal.

Notice that in the beginning, we are already separate. Only a small footbridge stands between us, but we are separate, nonetheless.

Here Nietzsche is hinting at the ontological nature of separation. Separation is there from the start. He offers no account of why, how, or when this separation occurred. It simply is.

His aphorism goes further, however, because in it one of them withdraws from the other. He shows that we deepen our own estrangement and alienation by refusing the invitation to communion and turning towards the “I” – a turning that will matter for us later. In that self-focus, we lose sight of the vision of “us” we once held. And all that’s left is space.

We fill this space with obstacles – Nietzsche’s mountains and rivers – and lose sight of the ‘other’. Yet unconsciously, we remember. We remember the footbridge, the other, and the possibility of union. That remembering becomes longing, desire, striving, affliction. And this separation is devastating.

As powerful as the image is, Nietzsche’s footbridge doesn’t quite satisfy me. At least two problems stand out.

The first is one of voice: who is the “I” here, and who the “you”? Two beings, already separate – one inviting communion, the other rejecting it, entrenching themselves in the alienation of individuality. But who are they? And why are they separate to begin with?

The second concerns these mountains and torrential rivers. Potent symbols, yes, but of what? And how did they arise?

As intended, Nietzsche’s deeply playful aphorism leaves us searching for more. He points to the symptoms, but offers no diagnosis – and certainly no cure.

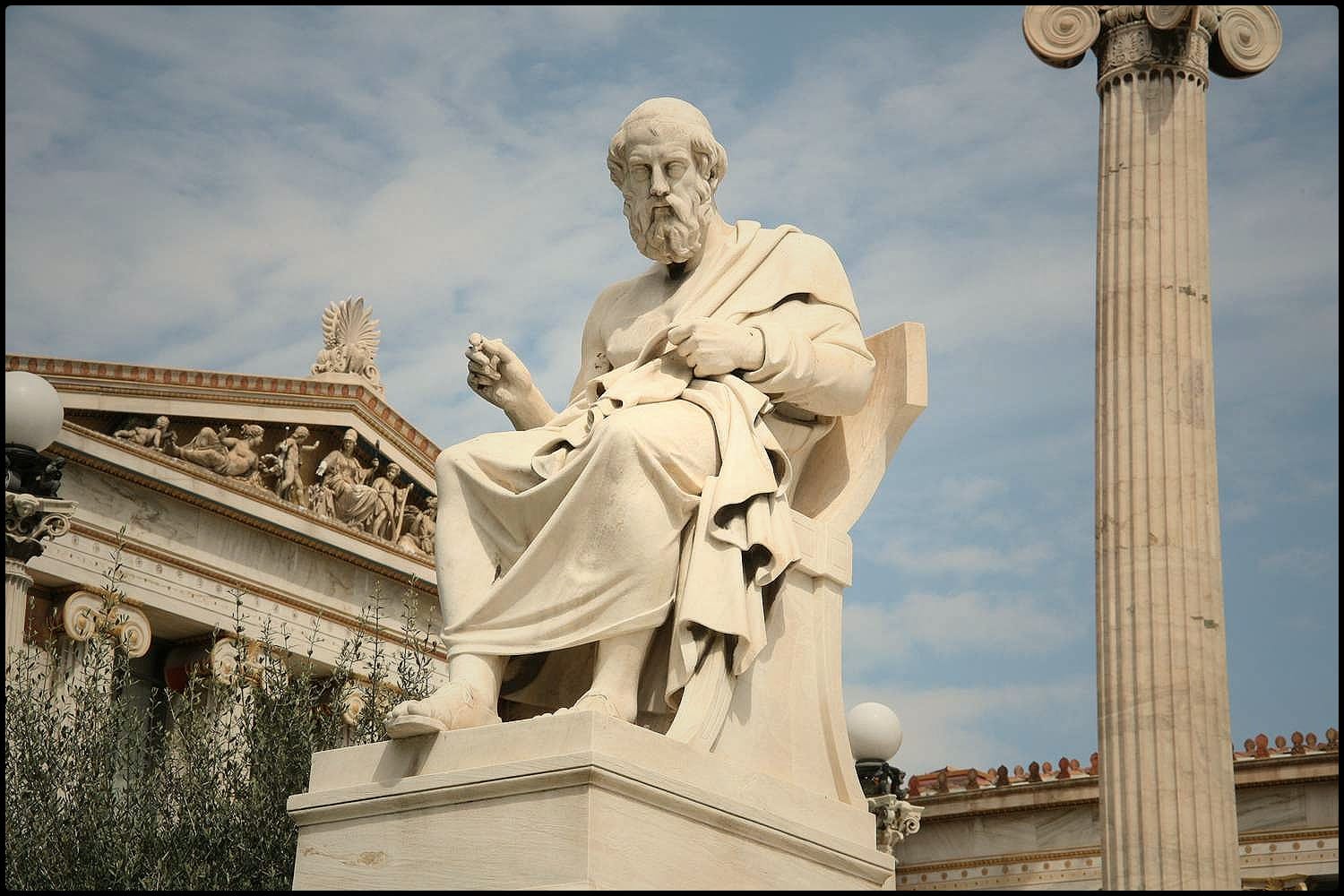

If Nietzsche leaves us in the ache of separation – a position we cannot accept – we might look back a few thousand years to a philosopher who refused to leave the ache unresolved. For Plato, the separation we experience is not despair, but a cosmic call towards harmony and order – a valley where Love itself mediates between the fallen soul and the luminous “Good”.

Plato’s Chariot and the Birth of Love

There are two strands of Plato’s vast thought I want to focus on here, because I think they shed light on this problem of separation. The first is his metaphorical soul as a chariot. The second is his conception of Love - a daimon or mediator that stands between the gods and the earth. Both are significant Platonic responses to our topic of separation.

To set the symbols in context: Plato had intuited a realm of Forms – eternal patterns of perfection, beauty and the good that break into the finite and luminate our sensory world. For Plato, this visible world is an arena where the finite things (like us) participate in the Forms. A world created from chaos and turned towards order and harmony by the gods. His later thought developed this further, positing an ‘ultimate good’ that was at the centre of our striving. As he said:

“The good is what every soul seeks, having an intuition of its reality but not knowing what it is” - The Republic

When placed alongside Nietzsche’s footbridge aphorism, the parallel is striking. If Nietzsche’s “I” is the Good, then his “you” is Plato’s seeking soul that remembers and yearns. The two converge, with Plato supplying a metaphysical structure for the sense of desperation and sadness that underlies Nietzsche. Fortunately, Plato goes further, and shows us how the soul can navigate this separation.

The Chariot

In the Phaedrus Plato depicts the soul as a chariot drawn by two horses under the charge of a charioteer. One horse is “good”, and one “bad”. The “good” horse, representing reason, is disciplined, sees beauty and is drawn towards the Form of the Good. The “bad” horse – representing passion – is unruly, impulsive, and seeks to seize and possess. It wants to own the Good. In this passionate desire to possess, the “bad” horse charges forth into the awesome light of beauty and ultimately stumbles and bucks at its sheer luminosity and goodness. At this moment, the horse pulls down. It turns the chariot away.

The driver’s role – our role – is not to destroy the lower horse, but to order and harmonise the pair. To control the desire to possess. To realign with the ultimate “good”. To bring order and balance between reason and passion.

You might ask – Why bother? Plato has a metaphorical answer for this too: We must bother, because the “bad” horse is not evil in itself; it’s desire still gestures towards the Good, but it seeks possession rather than participation. When it lunges to seize the Good, it fails.

Think of your eyes looking at the Sun. If you try and see it whole, your eyes are blinded and forced away. But accept its power, squint and shade your brow – and you can glimpse some of its beauty. This represents the two horses approach to the Good.

For Plato this tension explains the pain of longing. The ache of separation. Because for him, we cannot not strive for the Good. In fact, all that is “bad” in us, is simply a reflection of our finite, materialist self, striving for the Good in all the wrong places.

Plato would reject the ethical dualism that later philosophers would endorse. There is no “good vs evil”, simply the Good and a soul turned away from it. For Plato, all of creation is grounded in this infinite Good, and let’s not allow our finite selves to distort this.

Plato also relates this striving to pain, an existential anxiety. He says that as the soul perceives manifestations of the Good in the world around it – in art, science, politics etc – that it starts to remember the Form it once knew. This act of remembrance produces a painful longing – the growing pains of the metaphorical wings – and the soul begins to strive upwards.

This ache, this transformational turning, evidences the Good’s reality: the pain drives the soul forward, towards what it recognises to be true.

Mapped on to Nietzsche’s image, the “I” in the aphorism is the Good, and the “you” is the soul – it is us. The reason we refuse the invitation to cross the footbridge is that the “bad” horse, representing the finite, transient, materialist aspect of our being, prefers its own nature. Training the horse requires curbing its appetite – and this feels like loss. Because that appetite offers immediate pleasure. Power. Status. Wealth. Luxury. That doesn’t mean these things don’t in themselves contain the Good, in fact, they probably do, that’s why they’re so appealing. But they are not the Good. Like us, they simply reflect it.

Plato helps us understand Nietzsche’s mountains and torrential rivers and whatever separates and alienates. Because these are the obstacles built by the soul ruled by appetite, passion and desire. They separate the soul from the Good, not because the Good is not present, but because the soul has turned away from it as the centre of its striving, and placed other transient, reflective things in its place.

We see this everywhere around us today – in politics, religion, entertainment and the arts – a fixation on transient forms that reflect the Good mistaken as the source of Goodness itself.

This is an error.

An error that orients the soul towards finite things and assigns ultimate value where it does not belong. An error that entrenches the desire to possess and dictate, that reinforces the separation between us. An error that perpetuates the forgetting of the Good – and the horror of Love’s absence.

An error that allows a father to confuse the infinite Love that mediates the spaces between us with the desire to grasp and possess his child.

This brings us to the paradoxical heart of the chariot. As a metaphor, it illuminates Nietzsche’s aphorism and reveals the ontology of separation. It exposes the structure of our longing, but not yet its cure. We remain in existential anguish, cut off from the Good – still separate, weeping in the gulf between the finite and the infinite. Nietzsche’s concluding ache endures. For the wound to heal, for communion to be restored, the footbridge must be rebuilt. Another force must enter the space between.

For Plato, this is where Love comes in.

Plato and Love

In the Symposium, Plato tells the myth of Penia (Poverty) and Poros (Plenty), whose union produces Eros (Love) – not a god, but a daimon suspended between lack and abundance. Eros desires the Good and the Beautiful yet can never possess them.

In this role, Love becomes the mediator, not just between poverty and plenty, but between the infinite and the finite, the divine and the human. Love bridges the space between fallen, searching souls, and the luminous reality of the Good. Love becomes the force that draws the soul upwards, out of appetite and into participation with the eternal.

In this way, Love is precisely the little footbridge that Nietzsche remembers. The mediator that makes union thinkable. Because even when, in the midst of our restless desire to possess and hold, we fail to recall the ultimate Good, we never completely forget the little footbridge. We never completely forget love. We feel the ache of its absence – the absence of what we have turned away from – the longing and quiet terror of recognition.

Plato’s love, however, is still an upward movement – the soul’s striving ascent towards the Good. It is beautiful, but incomplete. What happens, then, when the Good itself, through Love, turns to us, and descends? What happens when the “I’ of Nietzsche’s aphorism finally says, “Enough – I am coming to you”?

Because, in a strange and fascinating continuation of Plato’s metaphysics, this is precisely what happened – and what happens still, every single day.

Simone Weil and Separation as Grace

Nietzsche doesn’t tell us why we’re separate, or even who it is that’s separate. He doesn’t tell us where this little footbridge – or the rivers and valleys that divide us – came from. Nor does he tell us how to find our way back.

Plato, by contrast, does. He explains who is separate, and why, and gestures towards a mediating force that might reunite us. Then he stops. There’s a historical reason for this silence – one I won’t name outright, in fear of taking you down a path you may not yet be ready for.

But let’s allow Simone Weil, the brilliant French philosopher and mystic, to take up Plato’s thread and unfold it metaphysically.

By the time we reach Weil, the Good has become God. Yet, for her, God is not a “thing”, not even a “being”. In fact, “He” is the opposite – a no-thing. For how can something eternal, outside of time and space, be as other beings are? This is the apophatic or negative tradition of theology: we cannot grasp God, because God is not a thing to grasp. God is beyond things – the sustainer of all things, the ground of all things that exist, not one more item within them.

Here, Weil and Plato converge: God is the unknown towards which we strive; the ultimate Good, the source and measure of all value.

“God is good. All the time. And all the time. God is good.”

You’ve heard that said – or sung – perhaps? But think about it metaphysically. It runs deeper than most people ever imagine.

For Weil, the very separation we feel – the ache of distance lamented by Nietzsche and illuminated by Plato – is not a flaw, but a necessity of the Good. Without space between us, where could Love dwell?

Imagine, for a moment, that you have a loving father (maybe you do, maybe you don’t). Now imagine you had never been born. Where would that fathers love be? So, where lies the Love? Not in the beings themselves, but in the space between them.

Weil takes this one step higher. She sees the whole of creation, distinct from God, as the ultimate act of divine love – God’s self-emptying into being. The space between us is not the Fall; our turning away from God is. The space between us is the possibility of love itself. As she writes in Some Reflections on the Love of God:

“God already voids himself of His divinity by the Creation. He takes the form of a slave, submits to necessity, abases Himself. His love maintains in existence, in a free and autonomous existence, beings other than Himself, beings other than the Good, mediocre beings. Through love, He abandons them to affliction and sin. For if He did not abandon them, they would not exist. His presence would annul their existence as a flame kills a butterfly”

That’s hard teaching. But look closely: it’s Plato’s metaphysics continued, and Nietzsche’s footbridge reframed. We are separate because we must be. Because separation is a condition of our existence. To not be separate, would be to not exist, and existence, Weil says, is inherently good. She continues:

“we are at the extreme limit…as far from God as it is possible for creatures endowed with reason to be. This is a great privilege. It is for us, if He wants to come to us, that God has to make the longest journey. When He has possessed and won and transformed our hearts it is we in turn who have to make the longest journey in order to go to Him. The love is in proportion to the distance”

In Weil, the very void where we weep – separated, alienated, fearful – becomes the alter of communion. God’s absence, our separation, becomes the condition for grace. And this changes the whole experience of separation: not as a curse to be suffered, but as a mystery to be endured and transfigured.

Yet, this transfiguration is not something to achieve or grasp. For Weil, too much action is the obstacle. Like Plato, she sees the placing of ultimate value in finite objects as error – illusions of misplaced worship, idolatry. But this can be remedied through what she calls decreation – the act of refusing to worship that which we know is not the ultimate Good. Which is almost everything, as it turns out – including the idea of God, which obviously, is not God.

In decreating, we recreate the space – the sacred emptiness – that might once again hold the little footbridge:

“The evil that we see everywhere…is a sign of the distance between us and God. But this distance is love and therefore it should be loved…If we love only through what is good, then it is not God we are loving but something earthly to which we give that name”

Here, Weil gives us our prescription: stop and decreate. Sit in the void. Feel it. Attend to it. And above all, wait. Not passively, but attentively. Focus on the Good and wait for God.

And something happens in this waiting.

God – the Good – Love itself – comes to us.

Weil see’s Love not only as a Platonic mediator between the finite and infinite, but as God’s own descent: the self-emptying of divine goodness into the world. In Christian traditions this is called kenosis – the incarnation of love.

We can strive for the Good, strive for God, but Weil reminds us that this striving can itself reinforce separation. Our task isn’t to strive, but to make space for God’s descent.

Weil tells us to clear the rivers and valleys, to become still, and to wait. Because God, incarnate in Love, will come – and be the little footbridge that carries us home.

In this way, Weil completes the circle of Nietzsche and Plato. The affliction we experience, and the love that heals it, are one. This void, when rightly attended to, becomes the site of grace. And in decreating the space between us, we allow Love to descend – and become the reconciliation of all that is separate.

A Fathers Lament

What does this all mean for me and my daughter?

I think it means this:

It’s not about loving someone ultimately.

We can’t do this, because we are not Love itself.

To try would be to place infinite meaning in my finite life.

To grasp love. To control it. To Use it. To turn from it.

But what I can do, is cherish, hold and free the space between us.

What I can do is let Love break into the void that separates me and my children –and reflect it back to them with all my strength.

Not in striving to be, but in witnessing what is.

To invite them into communion with the Good, and the Beautiful.

To invite them into communion with God.

And maybe that – fragile, human and trembling as it is – is the highest form of love that we can know.

And if it is, then it is enough.

Because what this recognises is a love that refuses to possess.

A love that waits.

A love that attends.

A love that hopes.

A love that, in its ache, reveals and recognises the God

who crosses the footbridge to us.

And a love that thanks Him – every second, of every minute, of every day –

for this gift.

Even though it’s a love that asks for nothing in return.

CODA

This has been, in essence, a brief philosophical exploration into ontotheological metaphysics. If you’ve not wandered these paths before, it can be a lot to chew on. We’ve travelled quickly through three very heavy thinkers in a discourse on a very heavy theme. Because, as I’ll explore in a later piece, this essay isn’t really about separation. It’s about sin.

So yes – you’ve just read through a dialectical meditation on the nature of sin.

Did you think that’s how your week would go?

Don’t worry if not everything made sense. Just sit with it.

How does it feel?

Sad? Joyous? Frustrated? Angry?

Which parts, if any, provoked a reaction?

Because that’s the true beginning of philosophy.

Not comprehension – but contemplation.

That’s where the training of Plato’s “bad” horse begins.

In the spirit of transparency, this piece could have gone in many directions. I chose Simone Weil as the synthesising thread because she resonates with me.

I’m drawn to her like Jonah to the Whale. Compelled. Summoned. Forced.

But others would tell this story rather differently.

Nietzsche would take the void as a call to power.

He would say: ignore the Good, conquer the void and place your own constructed “good” within it. Fill the void with an act of creation - and worship it as absolute. For him, orienting towards the Good was an orienting towards slavery.

But I’ll risk the heresy: wasn’t Christ the liberating, creative, abundant Übermensch that Nietzsche longed for all along?

Schopenhauer, who paved the path for Nietzsche, answered otherwise: Reject the striving itself. Stop willing. Cease the chase. Get out of the chariot.

Of course, for Schopenhauer this non-striving in itself, was seen as “good” and therefore something to strive for. Make of that what you will.

Albert Camus – Weil’s companion in thought, if not faith – would have said: face the void, demand nothing, there is no meaning, but strive for it anyway.

He was a braver soul than I.

Or there’s Heidegger, who might say:

“What void? What separation? You’ve misunderstood. There is only Being. Forget this talk of Separation, Good, God and Sin! These are all ontotheological confusions! Part of Being-in-the-world. Start BEING!”

Perhaps Weil would agree...he might have a point.

So the next time you find yourself longing for home,

yearning for the arms of an absent lover,

or struggling to love as you wish to love –

just pause.

Consider that this longing, this ache – is perhaps just the reflection of the ultimate Good for which we strive.

Or perhaps it’s nothing.

But perhaps, just perhaps,

that thought will put a quiet smile on your face.

And then someone, noticing this, will ask you:

“What are you thinking about?”

And with a deepening grin, you’ll reply:

Nothing